Incept date: 2024.03.30

(Under construction, being peer reviewed)

Audio power amplifier manufacturers have engaged in the “more watts is better” numbers war for so long, most people now think it’s the most important criteria in an audio amplifier. Watts have about as much do to with how good a stereo sounds, or how loudly it can play… as car horsepower ratings have to do with how well your car corners or it’s top speed. In other words not much and not directly.

Focusing solely on amplifier wattage numbers obscures much more important parameters for sound levels and quality reproduction.

tl;dr

A 3 dB SPL increase is barely perceptible, yet takes 2X the amplifier power in watts.

A 10 dB SPL increase is perceived as about twice as loud, but requires10X the amplifier power in watts!

First, some terms and basic info

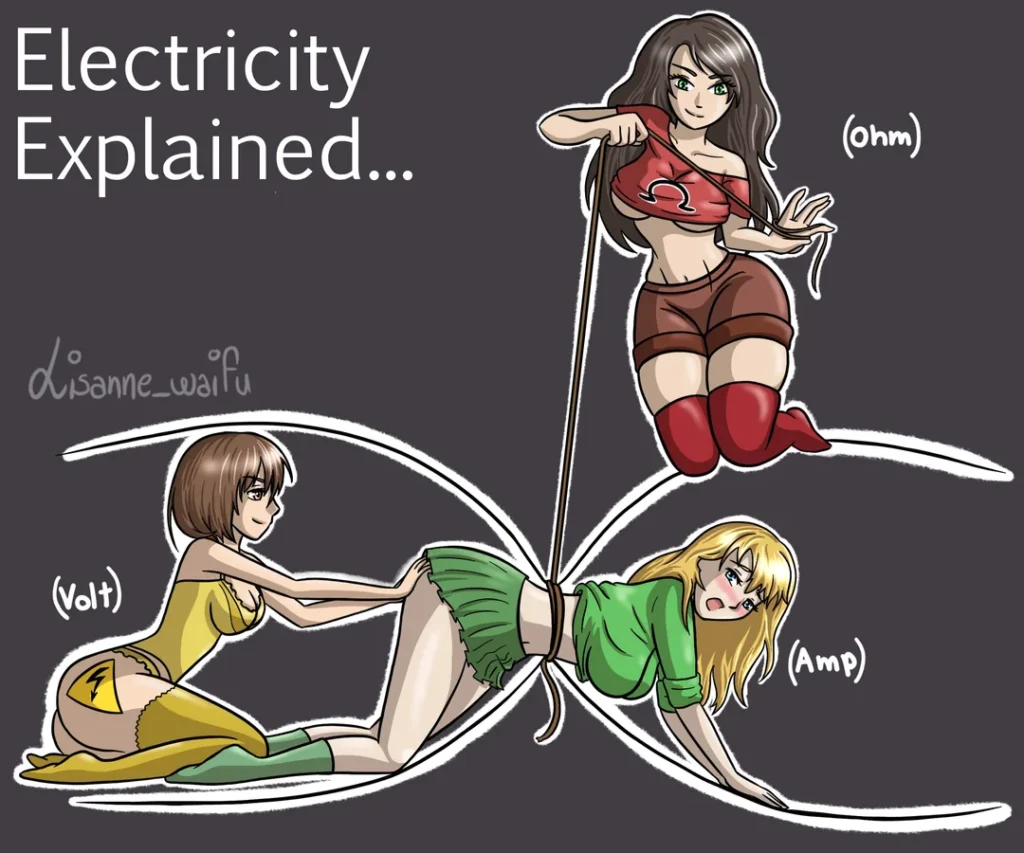

Watts are a simple measurement of electrical power. But before you can understand watts, you have to first understand the cornerstone formula of electricity, Ohm’s Law.

Don’t worry, it’s a simple algebraic formula. It states the basic relationship of electricity is V = I x R, where V (or E) is Voltage in Volts, I is Current in Amps, and R is Resistance in Ohms.

This amusing pic shows these basic parts and their function:

Where Volts is akin to a pressure pushing Amps along, but working against them is the constriction of Resistance.

Or something. 🙂

Notice this basic equation can also be stated as

I = V / R or Current = Voltage / Resistance

or

R = V / I or Resistance – Voltage / Current

meaning if you know two of these values, you can always calculate the third.

Importantly, and with all three values in hand, you can figure power in watts with this formula: Watts = Volts x Amps.

For example if your amp outputs 8 volts into 8 ohms, that means there is 1 amp of current. 1 amp of current at 8 volts is 8 watts.

*Note: This is a simplification based on easy to understand DC voltages. Audio is actually an AC signal and a bit more complex in the details, but the basic principles remain the same and the figures are close enough for this introduction.*

Yet, still this watts thing has nothing to do with sound.

Sound: Sound is what our ears perceive, generally agreed for young adults to be a range of about 20 Hz (very low bass) to 20,000 Hz (very high treble). We call this range the audio spectrum.

– Sound moves through the atmosphere at 20 °C (68 °F) at bout 343 m/s (1,125 ft/s, or in more useful terms for hi-fi, that’s about 34.4 centimeters or 1.13 feet per millisecond. Altitude and temperature affect the speed somewhat and in other mediums sound can travel at vastly different rates. The speed of sound means relatively small changes in distance are readily discernable and typically perceived as directional cues.

Age, gender, and noise exposure can have a profound effect on your hearing. Aging decreases your high frequency perception, much more so for males than females. It’s not unusual for 50 yr old males to not hear much above 8 kHz.

Sound Pressure Level, or SPL: SPL is a way to measure how loud a sound is. For audio work, it is typically measured in deciBels, or dB. Sound is perceived in a non linear fashion, like many things in the real world. Using a log scale to quantify it more closely maps to how our hearing actually works, and also reduces the numeric scale to something manageable. For audio, this scale usefully ranges from about 50 dB SPL(quiet living room) to 110 dB SPL (studio control room rockin’ out).

Note that only a few minutes of extremely loud noise exposure will permanently degrade your hearing.

Another non intuitive point to note is a 3 dB SPL increase is barely perceptible, it’s a 10 dB increase that is perceived as twice as loud. But that small 3 dB takes twice the amplifier wattage power, and that 10 dB (twice as loud) takes ten times the amplifier power in watts! (More on this later.)

As our hearing is rather non linear in terms of measurements, and those non linearities change based on the SPL, a variety of “correction factors”, or weightings are often used as well, with “A” and “C” weighting historically being the most common.

Another interesting property of sound is as it moves through the air from it’s source, the intensity (SPL) decreases by the square of the distance. Yep, another non linear scale.

IOW, for every doubling of distance, the SPL will be attenuated by approximately 6dB. As an example, a speaker generating 100 dB SPL at 1 meter will drop to 94 dB at 2 meters, and 88 dB at 4 meters.

So a proper SPL measurement would be specified like 88 dB SPL(A) and include the reference location, i.e. 1 meter on axis from front of speaker, or at ear position, etc.

For reference, being exposed to 91dB SPL(A) for 2 hours, or 106 dB SPL(A) for 4 minutes (i.e. about one pop songs length) will likely damage your hearing, often permanently.

Loudspeaker, or Speaker: A magical device that converts an electrical signals power into an acoustic soundwave. This is a most difficult transition to do well, and there are a wide variety of ways to accomplish the task. There is also a wide variety of ways to measure the successfulness (ie accuracy) or lack thereof, of this conversion. Frequency response, dispersion, dynamic range, various distortions, the rooms acoustical properties, and even the speakers location in the room are all parameters that influence this conversion.

One very poorly understood specification is the sensitivity specification, or at what SPL (see next section) the speaker will generate with a standardized reference signal at a standardized reference distance and location. This has a lot to do with how much power you need from an amp for a given speaker to achieve the desired SPL.

Audio power amplifier: Often shortened to “amplifier” or “amp”, although those terms are used in a myriad of other ways that can be confusing, so watch the context.

This is the last active electronics stage before your speakers. The amp provides the “muscle” (or power) for the speaker to do it’s thing. Note that the speaker and the power amplifier can (and do) interact with each other in complex and difficult to quantify ways.

Amplifier power is traditionally, yet misleadingly, specified in “watts”, which via ohms law is merely voltage (“V”, in volts) times current (“I”, in amperes).

Amplifier specifications and other games.

People like simple answers to complicated questions. And the nice thing about wattage specs is they seem simple: some is good, more is better, right?

Ummm, not that simple.

First off, a number without measurement conditions is just a number. And is suspect.

In the early days of high fidelity, amplifier power specifications and conditions were selected by the manufacturer as a way to make their products look better than the competition.

As time went on, this escalated into out and out wattage wars, where ridiculous conditions were used to get the largest possible wattage number for the marketing materials. A 1 watt amp (like an inexpensive stock car radio) could get rated as 10 watt amp if you ignored how distorted the audio it was… or a 100 watt amp if you overdrove the amp, shorted the speaker connection and measured the max instantaneous current before the amp self destructed. Ratings got so ridiculous the FTC and several trade organizations stepped in with some standard methods to allow rational comparisons. This standard “wattage” spec might look something like “80 watts per channel into 8 ohms, from 20Hz to 20000Hz, both channels driven, at less than .1% THD”.

Better, but even so a wattage spec is still a fairly useless gauge of an amplifiers ability to generate a desired SPL with your speakers, since it doesn’t factor in the speakers sensitivity and impedance curves. Also, the relationship of amp power out to speaker loudness is another nonlinear relationship, and further, the speakers impedance will vary with frequency.

(For this discussion, impedance may be thought of as a complex AC version of resistance, with other AC unique factor to complicate matters further. And if the impedance varies, so does power; remember ohms law? )

Wattage also doesn’t cover other key amplifier parameters, like the amps noise floor, types and levels of harmonic distortion, the more abrasive Intermodulation distortion, damping factor & output impedance, slew rate, frequency response at 1 watt, power bandwidth, dynamic range, overload characteristics… And whatever else I’ve forgotten off hand.

As if that isn’t complicated enough, all audio electronics have a limited range of conditions they work well in. For a power amplifier, too little signal means you won’t get your max amplifier power, or worse your signal will be buried in the noise floor.

And too much signal (overdrive) will cause the amplifier to exceed it’s power ability and go non-linear. The most common form of overdrive distortion is called clipping, and it is both horrible sounding and possible dangerous to your amp and speakers. You want to operate your amp in the sweet spot in it’s designed range.

So, what *is* important?

Ok, so why all the previous dull definitions? The point is in hi-fi, you don’t really care about watts, you care about how good your system sounds. Part of “good” can be measured, and part of “good” is your personal perceptions and musical preferences and your speakers and the room; all these are part of a complex system.

Notice that “Can it play stupid loud” is way down my list (and should be way down yours too), but “can the system achieve a satisfying sound level” is a valid criteria.

Armed with all that, we can now discuss audio system goals. But first, let’s get the power thing out of the way.

Example 1:

I have a pair of Klipsch Heresy 3 speakers with a quoted sensitivity of 99dB @ 1 meter using a standard reference signal of 2.83V (which is the current way of saying “1 watt into 8 ohms”, the old reference standard). If I listen from a distance of 4 meters, that “1 watt” will produce about 87 dB SPL at my listening position. OK, that 1 watt is plenty loud for me…

But wait! Music isn’t static test tones, it has dynamic range! If the music has modest 10 dB peaks, then I’ll need an amplifier with more power to handle those peaks, in this case 10x, or 10 watts. And if the music has a more realistic 20 dB peaks over average, then I would need 100x the power or a 100 watt amplifier for those 107 dB peaks!

Since 107 dB is too loud for me anyway, I just turn down the volume to an average of 77 dB, which leaves just enough headroom for the +20 dB peaks @ 97 dB on my theoretical 10 watt amp at my listening position.

The fact that I’m using a 30 WPC tube amp (3x watts) means I have a modest 4 dB of extra dynamic range headroom. Cool.

Example 2:

Another pair of speakers I have are “book shelf” sized Pioneer SP-8541-LR, rated at 89 dB @1W/1m.

So that means 1 watt is 77dB at my listening position, and a 100 watt amp would produce 97 dB SPL, yielding a healthy 12 dB of headroom when I listen at my usual 85 dB or so.

Since the speakers are rated for 130 watts max, they should be operating in their safe zone at that sound level as well, making this a good matchup, power to desired SPL- wise.

Remember:

A 3 dB SPL increase is barely perceptible, yet takes 2X the amplifier power in watts.

A 10 dB increase is perceived as about twice as loud, and requires 10X the amplifier power in watts!

Here’s a handy amp “wattage” table to consider. It uses a power scale which follows the SPL measurement dB perceptual scale, the dBW. I put an asterisk by the 1, 10, 100, and 1000 watt entries to highlight them.

Watts(RMS) to dBW

*1.0 = 0.0 dBW

2.5 = 3.98 dBW

5.0 = 6.99 dBW

*10 = 10.0 dBW

25 = 13.98 dBW

50 = 16.99 dBW

75 = 18.8 dBW

*100 = 20 dBW

200 = 23.01 dBW

250 = 23.98 dBW

400 = 26.02 dBW

500 = 26.99 dBW

800 = 29.03 dBW

*1000 = 30.0 dBW

1600 = 32.04 dBW

5000 = 36.99 dBW

Put a different light on those “watts” doesn’t it?

Still with me?

(following area under construction)

OK, let’s run some numbers for the Bose 901 speakers now.

I have a set of Bose 901 series VI speakers. Now Bose was (and still is) notoriously dismissive of specifications, but various folks have measured the sensitivity at abut 82 dB SPL @ 1 meter. That means 76 dB at 2 meters, and a rather quiet 70 dB at 4 meters. 10 watts would push it up to 80 dB, but it takes a 100 watt amp to get to a reasonably loud 90 dB.

(Actually, the SPL fall off in room isn’t quite that much due to the reflecting driver setup, but the 10x amp power requirement thought puzzle still applies.)

But wait! These speakers make use of an “active equalizer”, which is a purpose built equalizer tuned to modify and smooth the frequency response of the system. Electronically, this takes the form of about a 9 dB bass boost and about 11 dB of treble boost, relative to a 3200 Hz reference point. And we’ve already seen 10 dB means 10X power, so the amp needs to have a fair amount of power reserve.

The room:

OK, now practically speaking the acoustic space the speaker is in has an enormous effect on the sound, so one must factor that in too. My listening room has good acoustic diffusion and absorption, and measures about about 20′ by 18′ with an 8′ ceiling height. A modest size room of some 3000 cubic feet.

Addendum:

Theory and practice of how to hook up a 901 system.

Speaker to amp wiring

getting the polarity correct

active eq just before amp, post volume control

active eq in a “real” tape loop, pre volume control

– not for A/V surround receivers!

– testing for “real” tape loop (i.e. “insert” behavior

Daev’s notes:

2024.03.30 – Under construction

https://geoffthegreygeek.com/amplifier-power/

https://www.erinsaudiocorner.com/loudspeakers/bose_901_series_v/

Last Updated on 2024-04-12 by Daev Roehr